Giant sequoias — long survivors of the forest — succumbing to climate-driven wildfires

CAMP NELSON, Tulare County — In a recently burned stretch of forest in the remote southern Sierra, the charred corpse of a giant sequoia tree — 14 feet wide and 213 feet tall — stands out as a startling casualty of wildfire.

This article was published in the San Francisco Chronicle and written by Kurtis Alexander on Sep. 12, 2019.

The blackened trunk is not only bigger than the countless dead trees around it, but the conifer likely went centuries, perhaps 1,000 years or more, before meeting its demise two years ago.

This behemoth in the Giant Sequoia National Monument, though, is not the only sequoia to die in recent years. Up the hill, two more trees, only slightly smaller, were almost entirely burned and, not far away, three others within a few feet of one another perished. Go deeper into the grove and the death count rises above 50.

The giant trees, once thought to be unflappable fixtures of the forest and largely resistant to fire, are among the latest victims of climate change.

In the national monument’s Black Mountain Grove, as well as elsewhere in the Sierra Nevada, researchers studying the toll of recent wildfires are finding surprising numbers of dead sequoias. The losses, they say, are the product of bigger blazes fueled by warming temperatures on top of forests that have grown dangerously thick because of poor forest management.

“It’s alarming,” said Kristen Shive, director of science for the Save the Redwoods League of San Francisco, who since last fall has been surveying sequoias in the aftermath of wildfires. “I figured there would be one dead here or there, but the number we’re seeing and the extent that they’re burning is remarkable.”

The deaths, which have been observed in Kings Canyon National Park and as far north as the edge of Yosemite, are so shocking that Shive and others have become concerned that the species as a whole may be at risk.

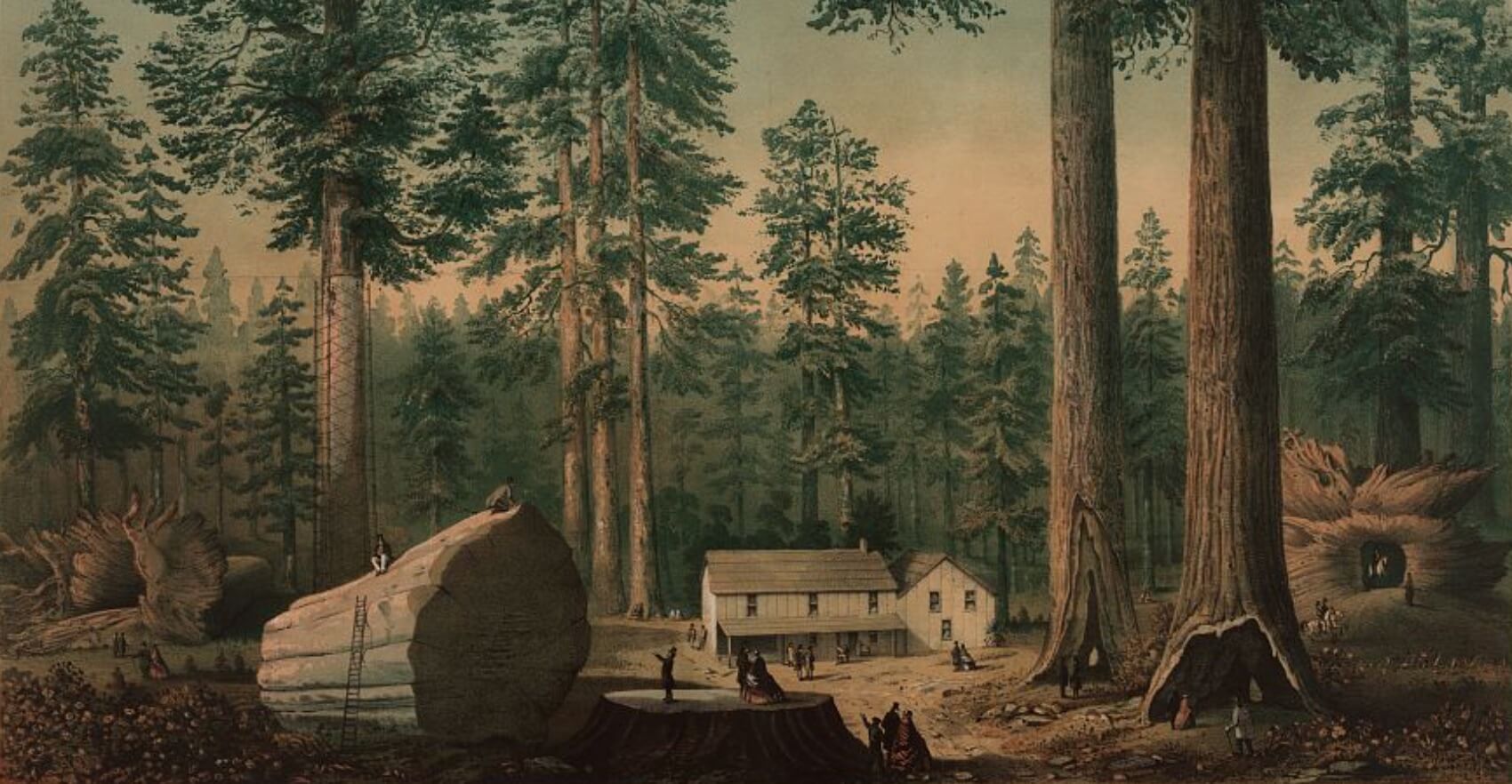

Sequoias grow only in a narrow belt of the Sierra, between Giant Sequoia National Monument and Lake Tahoe. They live within just 75 distinct groves. While related to the taller coast redwood, they’re bigger by volume and recognized as the world’s largest tree. They’ve come to symbolize the grandeur of the West.

“If it keeps getting warmer, as projected, we could see the deaths of sequoias happening more frequently and more extensively,” said Nate Stephenson, a research ecologist for the U.S. Geological Survey who has been studying the trees for four decades. “I would call it worrisome.”

Mature sequoias have long been considered impervious to fire, maintaining fibrous, hard-to-burn bark that can grow 2 feet thick and foliage that usually hangs far above the reach of flames. While wildfires have historically burned the Sierra landscape every decade or so, some sequoias have lived for 3,000 years.

Fire is also necessary for the tree’s regeneration, helping to open its cones and release its seeds, which then flourish in the burned, bare earth below.

“They’re the quintessential fire-resistant species,” Shive said on a recent visit to Black Mountain Grove, as she looked out at the unforeseen destruction. “Knowing that some of these trees were here when Christ was born, and to think some just got wiped out, it’s crazy.”

The 2,600-acre grove, which runs along a ridge high above the Tule River near the mountain community of Camp Nelson and its 100 residents, was hit by the Pier Fire in 2017. Flames swept through most of the sprawling stand of more than 500 big sequoias, mixed with ponderosa pines, white firs and incense cedars.

Shive’s recent surveys of the most intensely burned spots reveal that 53 sequoias with diameters of at least 3 feet died. Thirty-one of the trees had diameters of 10 feet or more.

The grove’s largest sequoia, Black Mountain Beauty, which measures more than 225 feet tall and nearly 20 feet wide, burned but survived.

Damage was similarly severe in the Sierra National Forest’s Nelder Grove, near the southern entrance to Yosemite National Park, when the Railroad Fire struck in 2017. Thirty-three sequoias with diameters of 3 feet or more died, said Shive and other researchers who surveyed the area.

Parts of Kings Canyon National Park and Sequoia National Forest have also seen significant losses of sequoias. The 2015 Rough Fire killed 12 trees with diameters of 4 feet or more in Grant Grove and at least 14 similar-size sequoias in Lockwood Grove, according to National Park Service surveys.

Tony Caprio, fire ecologist at Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks, said he began seeing an increased “susceptibility” of sequoias to wildfire just a few years ago.

“It’s not that they’ve never experienced fire damage,” he said. But “we really didn’t see much in the way of mortality.”

There have been exceptions, he said, but you have to go back a long time, for example, to a wildfire that killed several sequoias in the southern Sierra’s Mountain Home Grove north of Camp Nelson in 1297.

“Climate change is a contributing factor,” Caprio said, referring to the hotter, drier conditions that are helping drive the more lethal fires. And so is misguided forest management, he added.

For most of the past century, forest managers have pursued a policy of fire suppression instead of allowing the hills and valleys to burn, creating an unnatural buildup of vegetation that now provides ready fuel.

The fiercer fires that have resulted, researchers say, have gotten to a point where they can undermine the strong defenses of sequoias, destroying their crown or penetrating their bark and leaving them too weak or wobbly to recover.

“It’s daunting to imagine what this fire would have looked like to have been able to kill the trees,” said Andrew Latimer, a plant ecologist and professor at UC Davis who helped survey the dead sequoias at Nelder Grove this summer. “The flames must have been tall and intense. … It cooked them through their bark and burned their leaves.”

The wildfire also took out a footbridge in Nelder Grove and part of the popular Shadow of Giants Trail.

Researchers are looking into how much the recent drought may have stressed the sequoias and made them more prone to burning. Initial studies suggest the trees were not nearly as bad off as others during the dry years, which ran from about 2012 to 2017.

But Stephenson, with the U.S. Geological Survey, has found an additional problem. Some sequoias appear to be dying, not from burning, but from insects that are exploiting the tree’s weakened state after the combination of fire and drought.

He’s counted about two dozen trees, in addition to those killed directly by wildfire, that he thinks have succumbed to the native cedar bark beetle.

“It started attacking the trees at the top and worked its way down and managed to kill them outright,” he said. “Up until this drought, there had never been a record of a giant sequoia being killed by insects.”

Stephenson is still analyzing his findings, but he believes that the severity of the drought, the result of the warming climate, is largely responsible for the beetle kills.

Short of undoing global warming, researchers say giant sequoias stand a much better chance of survival with better forest management.

Reducing dense vegetation in the groves, with brush clearing and controlled burning, for example, reduces the likelihood of a blaze becoming so bad that it kills trees. A healthy forest also can be more resilient to insect infestation.

Where forest thinning has been done, losses of sequoias have been far fewer. For example, in Grant Grove, just one big sequoia died in the Rough Fire in areas where forest managers had preemptively burned, compared with 11 elsewhere in the stand, park officials reported.

In Black Mountain Grove, tree deaths were also fewer in parts of the forest that had more recently experienced burning.

Shive, with Save the Redwoods League, is watching to see what comes of the scarred grove. Already, carpets of bright green sequoia seedlings have begun to emerge on the forest’s ashen floor.

“It’s awesome to get the rejuvenation,” she said, pointing out a patch of roughly foot-high sequoias at the base of a dead tree.

Many of the grove’s giants, like in the other forests where sequoias have died, still thrive, which offers additional hope that torched areas will eventually rebound. Shive and other researchers note that even high-severity fires, at least in small doses, can be good for the trees.

She glanced at a giant sequoia that was badly burned but hung on to some of its scale-like leaves high in the sky.

“I think that one still has enough crown,” Shive said. “I think it will be OK.”

Kurtis Alexander is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: kalexander@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @kurtisalexander