From the distant canyons of Yosemite to the remote deserts of Death Valley, national parks are among the best places to escape the sounds of the city.

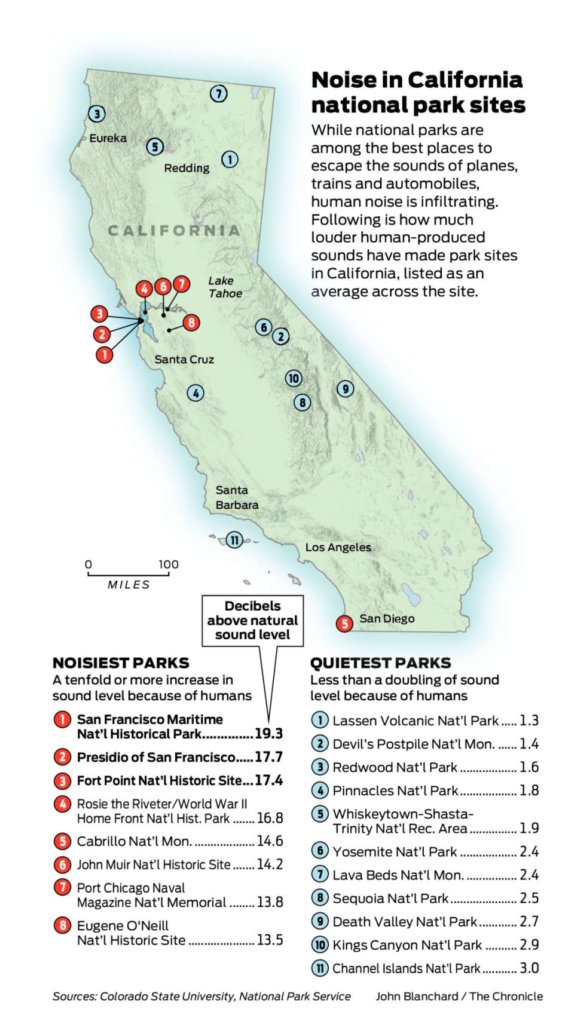

Yet, in an age of increasing thumps, buzzes and hums, noise is invading even this dusty turf. New research finds that 36% of national park sites in the continental United States are at least 10 times noisier than they would be otherwise because of human-produced sounds. Many of these spots are in California.

This article appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle by Kurtis Alexander on December 20, 2019.

The clamor, scientists say, isn’t a problem just for people grumpy about loud music and beeping iPhones. Noise has real effects on human health, contributing to anxiety and elevated blood pressure, for example. It also fouls things up for wildlife, which rely on an unobstructed environment to find food, escape predators and communicate for mating.

Sequoia National Park is only 2.51 db above natural sound level.

“It’s something that we generally don’t give much thought to,” said Rachel Buxton, a conservation biologist at Carleton University in Ottawa and lead author of the recent study. “You might notice a loud sound or something, but when you go into these areas and appreciate the natural sound, it is a resource and it’s under threat.”

The National Park Service has been working to limit human noise in some areas, including the giant redwood stands of Muir Woods National Monument, where a “quiet zone” has been put into effect. But in many parks, the intrusion of cars, jets and raucous tourists still trumps the chorus of a songbird, the bubbling of a creek or the howl of a wolf.

Kings Canyon National Park is only 2.93 db above natural sound level.

In the study published in October, Buxton and colleagues at Colorado State University and the park service modeled median noise levels at 364 sites managed by the federal agency across the lower 48 states. They analyzed 47,000 hours of audio clips and projected how sounds would travel given such factors as topography and road density. Their work appeared in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

The places they found to be the noisiest, ranked in terms of how much, on average, human noise raises the sound above natural levels across a site, are locations where commotion would be expected: urban parks and historic landmarks.

The park service’s loudest spot is Chamizal National Monument, a small park near downtown El Paso, Texas, that honors the shared culture of the U.S. and Mexico. It is rimmed on three sides by highways, including the Cordova Bridge, where one park interpreter described a constant flow of international truck traffic across the border.

Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site in Buffalo, N.Y., ranks second noisiest, and Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site in Arkansas ranks third. Fourth is the White House.

Because of human sounds, all of these places are more than 100 times louder than they would be otherwise.

Parks outside of cities, and in many cases celebrated for their unspoiled wilderness, also deal with human noise, where it’s usually quieter but often more problematic.

The Grand Canyon in Arizona, Arches in Utah, Rocky Mountain in Colorado and North Cascades in Washington are among the more primitive national parks that are at least twice as loud as they would be without human sounds, the study finds. So are California’s Point Reyes National Seashore, Muir Woods and Joshua Tree National Park.

“If you think of things like a bird courting another bird, that’s done through song, and a fox listening for a mouse in the snow, it’s hunting,” Buxton said. “By disrupting these sounds, we can have really big effects on an animal’s survival and reproduction.”

One study seven years ago at Grand Teton National Park found that noise from cars, bikes and pedestrians put elk and pronghorn at greater risk of being eaten by grizzly bears, gray wolves and mountain lions. The animals were presumed to have a harder time hearing their predators approaching.

Research has also shown that preserving the natural soundscape significantly benefits humans. Not only does spending time in wild places improve mood and memory, but not getting away from city sounds can raise the risk of cardiovascular disease, sleeping trouble, depression and general annoyance.

The distinction of quietest site in the park service, according to the new study, goes to Cedar Breaks National Monument, a far-flung red-rock canyon in Utah. The next quietest is Lassen Volcanic National Park, a geologically active area in sparsely populated Northern California. El Malpais National Monument in New Mexico, Great Sand Dunes National Park in Colorado and Devils Postpile National Monument in Mammoth Lakes (Mono County) round out the top five.

The most prevalent drivers of noise in the park system, the study finds, are cars and planes. When present, however, trains and boats are the loudest sources of noise.

The human sounds are largely localized, the study also finds, most observed around developed areas such as roads or train tracks. Even though noise levels are more than 10 times higher at more than a third of park sites because of humans, areas that are this loud represent just 2% of all park service lands.

The park service, since its creation, has been entrusted to protect the natural soundscape as part of its conservation mandate. But only in the 1970s did the federal government acknowledge human noise as a pollutant, and only in recent decades have park officials begun studying noise pollution and seriously trying to minimize it.

“There’s so much research on the benefits of natural sounds,” said Megan McKenna, an acoustic biologist for the park service and a co-author of the recent study. “It’s another resource like water quality. We protect the quality of the acoustic environment.”

McKenna is one of three park sound scientists based at Fort Collins, Colo., who have been working in collaboration with researchers at Colorado State University to diagnose and address noise in parks.

Their work, while still evolving, has spurred several noise-mitigation projects. Backup beepers on park vehicles in Alaska’s Denali National Park have been traded for more benign swooshing warnings, for example, and shuttle services and reduced speed limits have helped reduce traffic noise at many other parks.

In Muir Woods, at a stand of towering redwoods known as Cathedral Grove, park officials have created a designated quiet zone. A sign at the beginning of the grove, where ancient trees rise more than 200 feet tall, reads “Enter quietly.”

“We hope people take a moment to reflect and think about where they are and what the space means,” said Shalini Gopie, a public affairs specialist for Muir Woods.

The quiet zone has resulted in a significant drop in human noise, according to one study that found visitors could hear sounds from about twice as far as they had previously. The fact that the area is still free of cell phone service helps maintain the quiet.

The new reservation system at Muir Woods, which limits the number of visitors who can enter the Marin County site, has also helped preserve the natural serenity by spreading out visitation, Gopie said.

Yosemite and Sequoia/Kings Canyon national parks are much quieter than Muir Woods, owing to their location in the undeveloped Sierra. But human noise has still endured. One of the biggest problems is airplanes buzzing the skies, even in the most inaccessible of wilderness.

“You’re there and you’re there overnight, and you’re enjoying a quiet experience looking at the stars because you’re so far away from everything, and then you hear a flight overhead,” explained Sintia Kawasaki-Yee, a spokeswoman for Sequoia/Kings Canyon.

Because of the importance of hearing the sounds of nature, park officials at Sequoia/Kings Canyon opened a listening exhibit at Grant Grove Visitor Center last summer. The display includes recordings from different elevations and ecosystems, from lush meadows to thick forests to mountain peaks.

Park officials say the project makes it possible for people who can’t get to hard-to-reach spots to experience the sounds of the great outdoors. It also could benefit those who might make it to the backcountry but miss something because of a roaring jet.

“There’s the sounds of the rushing river,” said Kawasaki-Yee, describing the new exhibit. “And there’s the bighorn sheep clashing with their horns. That’s really loud.”

This article appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle by Kurtis Alexander on December 20, 2019.